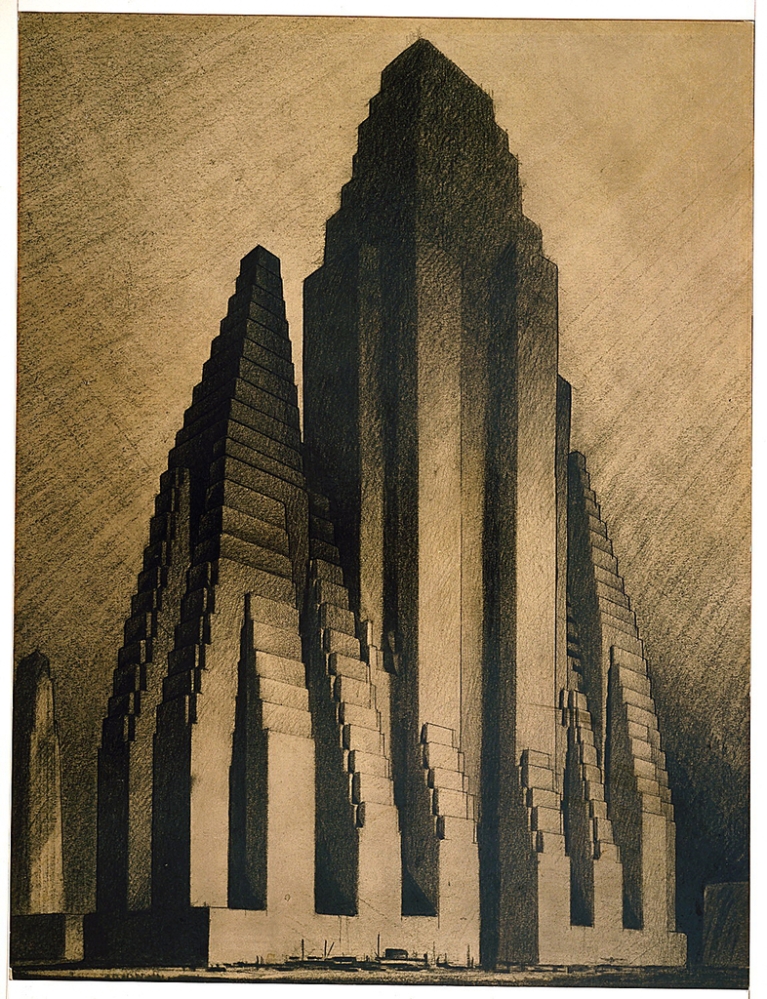

The article below was contributed to the Graphicine website by Roxana Wax. It features some of Hugh Ferriss’ most outstanding architectural and industrial drawings and sketches. As noted by Wax, Ferriss was a man whose visions weren’t appreciated during his lifetime, yet his influence is beyond dispute.

One aspect of Ferriss’ visions that stands out is the foreboding nature of his metropolis of the future. The structures, while beautiful in their lines and perfect geometry, are sometimes giant megaliths that dwarf all human dimensions. They are, in fact, indicative of the impersonalization of the early 20th century – the rise of the somewhat soulless vision of a mechanized bureaucratic system where civilization would now be measured by the size and style of its structures and buildings, rather than the former measures of culture like the arts (at the one side) and the simple beauty of the family farm (on the other).

It’s often pointed out that the structures which a culture builds far outlast all other impressions. This is clear from the ancient pyramids to the Grecian temple remains. While the pyramids left an enduring image of mystery and genius, and the Greeks left the imagery of beauty and thought, today’s structures are rarely built to last. One wonders, does Ferriss’ works relate more to the 21st century future still to come?

It’s no wonder that Ferriss’ works became an inspiration of dystopian metropolises like Batman’s Gotham – this is very much the essence of those visions the brilliant artist presents.

Roxana Wax

10 February 2014

Hugh Ferriss (1889 – 1962) was an American delineator (one who creates drawings and sketches of buildings) and architect. According to Daniel Okrent, Ferriss never designed a single noteworthy building, but after his death a colleague said he ‘influenced my generation of architects’ more than any other man. Ferriss also influenced popular culture, for example Gotham City (the setting for Batman) and Kerry Conran’s Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow

via Graphicine